1660s – The Pocket Watch, the Waistcoat and the Merry Monarch

The rise of the pocket watch began during the reign of Charles II with the introduction of the waistcoat. On 7 October 1666, diarist Samuel Pepys noted: “The King hath yesterday in Council declared his resolution of setting a fashion for clothes, which he will never alter. It will be a vest, I know not well how, but it is to teach the nobility thrift, and will do good.”

During the Restoration of the British Royal family, the Merry Monarch introduced the waistcoat into ‘proper dress’ in a bid to simplify royal fashion and distance his household from the flamboyant styles of French nobility.

On the outside of the garment was a small pocket designed to hold a personal timepiece, which sat flat against the body, and any watch that was to fit inside it would have to do the same.

Although pocket watches had existed for at least a century prior, they were bulky objects often worn around the neck like a pendant - to fit inside the waistcoat’s pocket, the watch would require significant modification. Consequently, during the late seventeenth century, the timepiece was adapted to become smaller, slimmer and, in the process, substantially more fashionable.

As a result, demand for pocket watches increased dramatically during the reign of Charles II, and the pocket watch became the first timepiece available for public consumption - even if just for those in the upper echelons of society.

1670s – British Ingenuity Prevails: Hooke, Tompion and the Race for the Balance Spring

In 1675, scientist and polymath Robert Hooke embarked on a collaboration with esteemed watchmaker and ‘father of English clockmaking’ Thomas Tompion to produce the world’s first spring regulated watch.

Renowned for never completing experiments due to his heavy workload at the Royal Society, Hooke became motivated to construct the spring regulated device after Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens produced a similar mechanism the year before. Although Hooke did not have a prototype by the time Huygens unveiled his timepiece, the experimenter cried foul, claiming he had presented the idea and theory to the Royal Society 17 years before in 1658.

The race was on, and in 1675, Hooke presented his timepiece to Charles II. To make their claim to the device absolute, Hooke somewhat petulantly inscribed, in Latin, upon the watch’s case: “Hooke invented this 1658. Tompion made this 1675.”

As it turns out, neither Hooke and Tompion’s nor Huygens’s mechanisms were accurate enough to be granted the patent. However, the concept would prove revolutionary to the advancement of timekeeping, improving the accuracy of portable timepieces from around an hour a day to a matter of four or five minutes.

From here, British horological progress moved with vigour, accelerated by a cocktail of the technological advancements catalysed by the Industrial Revolution and the emphasis on reason and scientific discovery promoted by the great thinkers of the Enlightenment.

1680 – Daniel Quare, Some More Tompion and a New Escapement

In around 1680, Somerset-born horologist Daniel Quare invented the first repeater mechanism. Designed to aid night-time timekeeping, Quare’s repeater announced the time in fifteen-minute intervals with alternating chimes – no longer was it necessary to light a candle or oil lamp to know the time during the darker hours. Later versions of the repeater would include an additional third tone to represent minutes, signalling the dedication to progress timekeeping precision.

Then, fifteen years later, renowned British horologist Thomas Tompion invented a revolutionary mechanism: the cylinder escapement.

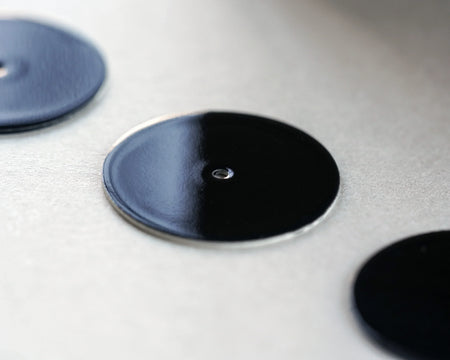

A small mechanism with a hollowed-out cylindrical balance wheel and horizontal escape wheel, Tompion’s cylinder was the first challenge to the reign of the verge and foliot escapement, which, up until this point, had featured in every timepiece globally for centuries prior.

Tompion’s cylinder escapement was a welcome development. The verge and foliot was notoriously inaccurate and could fall out of time by as much as two hours a day. The verge and foliot escapement was also a bulky mechanism, making it impractical for the increasingly popular and fashionable pocket watches appearing at the end of the seventeenth century.

The compact nature of the cylinder escapement made it substantially more suitable for use within pocket watches. Additionally, and more importantly, the cylinder escapement was a far superior timekeeper than the verge and foliot.

Tompion’s escapement replaced the pallet system employed by the verge and foliot with the hollowed-out cylinder. By doing so, he significantly reduced recoil - the problem that had caused the verge and foliot escapement to fall so far out of time.

However, much like the verge and foliot, Tompion’s mechanism was prone to excessive wear as a frictional rest escapement. French watchmakers attempted to rectify this by building the balance wheel from ruby, but this made the mechanism vulnerable to shock. As it was not self-starting, if jolted or shocked in any way, the cylinder escapement would 'set' or stop.

It would take another 30 years for Tompion's own apprentice and relative George Graham to perfect the cylinder escapement. Indeed, Graham's contributions to the development of the mechanism were so great he is often also credited with its invention.