Meet the Maker: The Man Behind the Method, Callum Robinson

Jul 03, 2024

Collaboration is one of the founding principles of anOrdain, and its spirit has taken us down some unexpected paths, and introduced us to some great friends. One of those friends and collaborators is Callum Robinson of Method Studio, the skilled carpenter and craftsman responsible for the undulating texture of our Model 3 Method. With his first book, Ingrained: The Making of a Craftsman, eagerly anticipated for publication in August, we caught up with him to learn more about his process.

The eldest son of a Master Woodworker, Callum spent his childhood surrounded by wood and trees, absorbing craft lessons in his father’s workshop, playing amongst the sycamore, oak and Scots pine that bordered his home. In time he became his father’s apprentice, helping to create exquisite bespoke objects. But eventually the need to find his own path led him to establish his own workshop; to chase ever bigger and more commercial projects, to business meetings, bright lights and bureaucracy, to lose touch with his roots. Until the devastating loss of one major job threatened to bring it all crashing down. Faced with the end of his business, his team and everything he had worked so hard to build, he was forced to question what mattered most.

Photo credit: Marc Millar

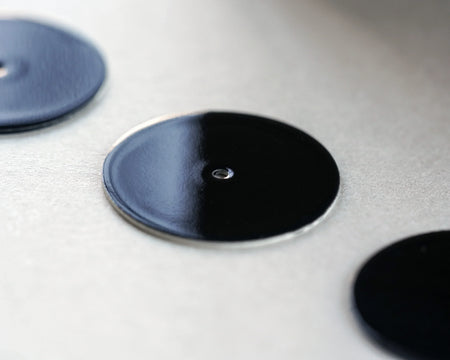

The wood that became the Method dial

The stamped dial blank

Wood is very accessible, which is something I’ve always loved about it. It’s versatile too, forgiving and tactile, and it smells fantastic.

Wood is very accessible, which is something I’ve always loved about it. It’s versatile too, forgiving and tactile, and it smells fantastic.

Wood carving in Method Studio

Method Lichen

Method Limited Edition Trunk in Ebonised Oak, goatskin and bridle leather

The Method Aqua on the wrist