Struthers 248 dial

Aug 18, 2022

One thing we don’t do at anOrdain is make enamel dials for other brands. It’s not that it wouldn’t be a nice thing to offer, but all our resources are needed for making our own watches. However, there is one very special exception.

We’re incredibly proud to have partnered during the past two years with Craig and Rebecca Struthers, the married couple behind Birmingham-based Struthers Watch- makers, to create the dial for their landmark new watch, the 248.

The 248 watch with anOrdain enamel dial

The first in-house movement by Struthers Watchmakers

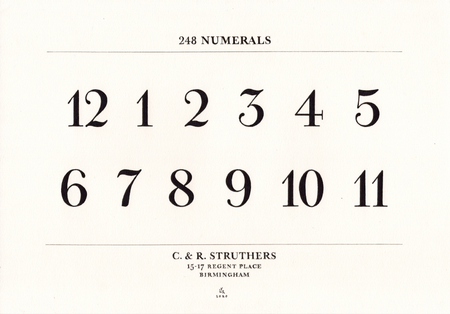

248 numerals designed by Lee Yuen-Rapati

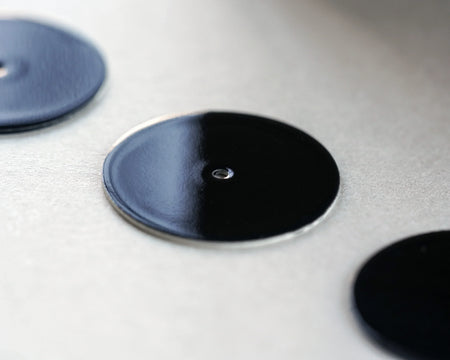

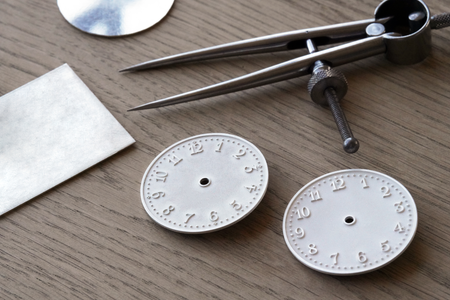

Dial blanks

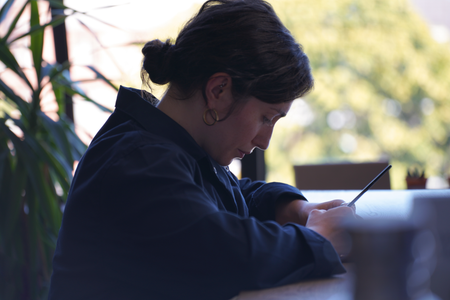

Sally enamelling the dial

Enamelling the dial

Using liquid enamel

The final Struthers 248