100 Years of British Military Watches - Part 1

Oct 23, 2018

Introduction

When it comes to military issued watches, there is probably no other country in the world that can match the incredible number, variety and quality of watches issued to its armed forces than Great Britain.

Upon realising that I had inadvertently collected British military watches covering the period 1914-2014, it seemed an opportune time to use my collection to tell the history of timepieces issued to HM Armed Forces over the past 100 years. Sadly, I don’t own an SBS Rolex Submariner or a Royal Navy Omega Seamaster, and many of the watches in my collection are neither particularly rare or valuable. None the less, they do tell an interesting story on the evolution of watches in general, and military issued watches in particular.

So just what is it about military issued watches that consistently attracts collectors, leading them to sell for significantly higher prices compared to equivalent civilian watches?

Well there are quite a few reasons that can broadly be divided into economic ie “reality”, and “fantasy” domains.

From an economic perspective part of the value of military issued watches lies their relative scarcity. Military watches are usually produced in much lower numbers than commercially available watches. And, you generally can’t just walk into a shop and buy one.

Service personnel, certainly in earlier years, were only issued with a watch if their role required them to have one. When issued, they remained the property of the Crown, and were supposed to be handed back in. The fact that they are Crown property is denoted by the broad arrow, or Pheon, commonly stamped on the back of watches, or sometimes seen on the dial. This is one of the reasons military watches have individual engraved issue numbers, so a note of which soldier was issued which watch could be taken, so that they would not “disappear”. Sometimes this would be noted in your pay book so if it was not returned your pay would be docked!

Another reason for the popularity of military issued watches, is that the military has specific standards to which issued watches must adhere, meaning that they tend to be produced to a durable high quality standard. With military equipment, form follows function, and in watches, this leads to highly legible and functional designs. Military watches therefore fall into the “tool watch” category, being built to be both highly functional and tough.

However, I would be lying if I said that military watch collectors aren’t also driven by an element of fantasy!

A typical military watch collector fantasy day dream might go like this …

“Was this WWI watch worn by a soldier going “over the top” at the Somme? ….. Was this WWII pilots watch worn by a Spitfire pilot participating in D Day? …… Was this Falklands era watch worn by a Para in the Battle of Goose Green?”

The answer is probably no, but you never know. Just as war has been described as months of boredom punctuated by moments of terror, the life of the average military watch is likely to be similar. Whilst for the vast majority of the time it probably timed nothing more exciting than when a period of guard duty was over, or made sure its owner didn’t miss last orders at the mess, certainly a proportion of military issued watches will have participated in historical military operations that have shaped the world we live in today.

So without further ado we will begin where it all started for wristwatches, World War One.

World War I

Prior to WWI, men used pocket watches. Whilst wristwatches existed, they were generally the preserve of upper-class ladies, and were regarded as delicate and feminine. However, this situation changed rapidly when troops became bogged down in the horrors of trench warfare.

The time and distraction needed to pull a pocket watch out of your tunic, pop it open, look at the time, and then put it away again, could literally mean the difference between life and death in the trenches of WWI. Enemy snipers were constantly scanning the front line looking for a target, and the time and distraction needed to look at your pocket watch could potentially be fatal. To address this, and other impracticalities of pocket watches in the trenches, soldiers began strapping pocket watches to their wrist. It was then a short step from this, to the first widely produced gents wristwatch in the world, the trench watch.

The trench watch in many ways can be seen as a transitional design between the pocket watch and the wristwatch. Whilst at first they were known as “wristlets”, within a few years the term wristwatch became prevalent. The now common wristwatch case did not yet exist, so small pocket watch cases, most commonly made from silver, were adapted by having wire “lugs” soldered onto them. Trench watches were purchased by troops themselves, and not generally issued by the government.

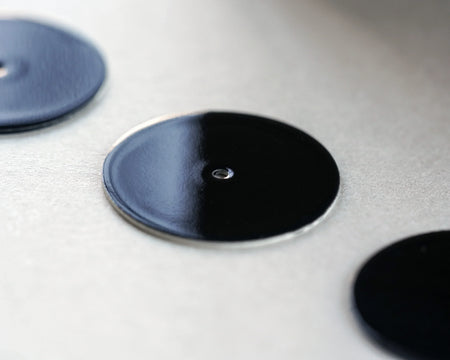

As the war ground on, a number of features began to emerge as standard on trench watches. Amongst the most useful of these was the use of luminous paint on dials and hands, which contained radium. Whilst highly effective in illuminating a watch at night, or in low light conditions, radium is highly radioactive with a half-life of 1600 years. This means that, to this day, such watches emit measurable levels of radioactivity, and potentially dangerous radium gas. Other common features were the use of water and dust resistant “Borel” cases, so called unbreakable glass and 24-hour numbers on the dial. Watch glass guards were also used to protect the glass from shattering on impact.

Later on in the war, it became clear that white on a black background is more legible than black on a white background, and this led to military watches adopting this classic highly legible format.

At the end of WWI, with it having been common to see battle hardened troops on leave back home wearing their trench watches, the wristwatch had lost its perception as being feminine and fragile, and was accepted as an item that could be worn by both men and women. However, the writing was now on the wall for the venerable pocket watch, as both fashion and the practically of the new wristwatch led to an inexorable decline in its popularity.

World War II

By the time WWII started, the wristwatch was well and truly established as an essential item for most men who could afford one. However, the British military had not entirely given up on the pocket watch as evidence by the “GSTP” line of pocket watches that were produced by a number of makers for the British armed forces. GSTP is thought to stand for “General Service Time Piece”.

In part this continued use of pocket watches may reflect a lag in adopting new items by the military when they already had a reliable, if older device in the pocket watch, and this pattern is seen later in the delayed switch to quartz. However, pocket watches could also have the edge when it came to accuracy due, in part, to the fact that they were mostly stored in one position (upright) in a vest pocket, compared to wristwatches that could be more susceptible to positional error.

Whilst the “Dirty Dozen” of British military issued watches are now well known, and command high prices, these were only issued towards the end of the war, around 1945. Instead the majority of the war was fought using the more humble “ATP” watch. ATP is thought to stand for either “Army Time Piece” or “Army Trade Pattern”.

Whilst these watches did have to comply with some specific standards in relation to, for example, night time visibility, the majority of these watches were pretty much identical to equivalent civilian models. Most of the cases of ATP watches were made out of chrome plated brass, although some were made from steel. The movements were manual wind, and had 15 jewels. A number of Swiss companies supplied these watches, and would not infrequently also supply near identical ones to Axis forces.

Whilst the watches supplied to the British Army could be somewhat basic, those supplied to the Royal Air Force (RAF) were usually of a much higher grade. The reason for this was the much higher accuracy that was required when airmen used a watch, for example, for navigation or bomb aiming purposes, compared to land forces.

An accurate watch could also literally mean the difference between life and death for an airman. For example, in the event of an instrument failure, it could be used to determine how much fuel was left, and consequently how much flying time was left. This could mean the difference between ditching in the Chanel or having a pint in the Officers Mess.

A wide variety of other time keeping devices were used by the British military in WWII. Below is an example of an 8-day cockpit clock, thought to have come from either an RAF Hurricane or Spitfire, and containing a Jaeger LeCoultre 8-day movement.

So far we have talked about the Army and the RAF, but let’s not forget the Royal Navy. Below is an interesting and unusual type of stopwatch used by submarines to determine the underwater distance of an enemy vessel. Known by the snappy title “Admiralty Pattern No 6 ASDIC stopwatch”, it measures half the speed of sound in water in seconds, and was used in anti-submarine operations.

It has been said that ASDIC stood for “Allied Submarine Detection Investigation Committee”, although it has also been stated that no such committee existed, and instead the term Anti-Submarine Division (ASD) is more accurate. Either way this group was tasked with developing methods to combat the scourge of the Atlantic U-Boat menace, that came so close to defeating Britian, by blockading supplies in WWII.

In terms of how it worked, you will doubtless all remember the SONAR “ping ping” sound from WWII submarine films. The operator would start the stopwatch at the first “ping”, which is the initial SONAR sound leaving the detection vessel. The operator would then stop the stop watch when they heard the second “ping” which is the sound being reflected back from the hull of the enemy vessel. The measurement from the stopwatch could then be used to calculate the distance of the enemy vessels, to facilitate the setting of pressure detonators on depth charges or timers on torpedoes to explode on target.

As WWII was drawing to close, the now famous “WWW” (wristwatch Waterproof) also known as the “Dirty Dozen” were issued in 1945. Produced by a dozen different Swiss manufacturers, these watches were produced to specific military standards and featured stainless steel “waterproof” cases, and high-quality hand wound jewelled movements. They also established the now iconic look of subsequent British military watches with matte black dials, “Sword” hands and white luminous painted hands and numerals. The rarest Dirty Dozen watches can reach five figure sums, but sadly my budget doesn’t stretch to one of these. However, please join me for Part II to explore the rest of my collection from post-war to Cold War.