Movement Watch #1 - Grand Seiko

Oct 23, 2018

The opportunity to see and handle some flagship - and limited edition - Grand Seiko watches came about thanks to Redbar Glasgow, who held a recent event hosted by James Porter & Son in Argyll Arcade.

My primary interest in attending the event was the chance to see Grand Seiko’s high-end, Japanese-made watch movements close-up, as some are remarkably different to traditional Swiss designs that I typically work on.

The Seiko Spring Drive

Spring drive1 movements are perhaps the most interesting, and by far the most graceful, of Seiko's quartz-mechanical hybrids. The novel serenety of its gliding sweep seconds hand is quite an experience in person, and for good reason - there's no mechanical escapement to interrupt the train, and likewise no electronic stepper motor to jerkily advance the seconds hand.

Instead an electromagnetic brake, quartz regulated and ultimately powered by the mainspring, exerts a continual drag on the gear train. Personally, I feel it marries the character of a mechanical movement with the accuracy of a quartz crystal very well.

Flipping the watch over, there was less to see through its exhibition case back. The self winding bridge obscures most of the movement except for the glide wheel - the small wheel in the spring drive that generates electricity for the circuit and electromagnetic brake. Sure enough, it was whizzing away like an escape wheel with the pallets removed.

Chasing the oscillating weight out of the way revealed another recognisable feature. Like the humble, middle aged Seiko 5 on my wrist, this very modern movement uses Seiko’s classic self-winding device. Just beside the ratchet wheel was the distinctive ratchet toothed profile of a transmission wheel, together with one pawl of the famous lever2 commonly referred to as the ‘magic lever’.

Above: The 'magic lever' pawl of a modern Grand Seiko movement next to the pawl of a 36-year-old 6309.

For decades, the "magic lever" has worked so efficiently that Seiko deleted manual winding from the crown functions on a wide range of its models. The system has been so dependable that its continued use makes good sense, whether in a modern flagship or workhorse movements stretching back to the 1950s.

The High Beat Movement

Seiko's 9S high beat3 movement uses a conventional lever escapement, vibrating at 36000 beats per hour. In rough terms, when it comes to accuracy of a timepiece, the greater the frequency of its oscillator the better. In the past, servicing considerations limited the popularity of 36000 bph movements. As a compromise between performance and reliability, 21,600 to 28,600 beats per hour (3-4 Hz) is fairly common in modern movements; it will be interesting to see what servicing intervals the 9S can manage with modern lubricants.

The examples on display had playful textured dials, but my eye was drawn to the balance, specifically the curious piece protruding 90 degrees from the index.

Above: A curious feature of the 9S regulator index.

Above: A curious feature of the 9S regulator index.

I couldn’t quite see its function through the caseback, either through a 10x loupe or while attempting macro photographs. It could be an exaggerated version of the Etachron4 system, with an even greater difference between the relative distances of the inner and outer curb pins from the stud.

On the other hand, it's more likely to be fixed to a rotating boot below the curb pins, something which is usually only accessible after removing the balance cock and turning it over. If so, one wonders why the high beat movement does not employ the same style of Etachron index installed in other Seikos.

Was the security of a traditional boot to keep the balance spring within the pins during a shock considered more beneficial in a 36000bph movement? Or perhaps such a high beat makes an Etachron-style consideration for spring flattening during supplementary arcs unnecessary. From photos of other modern 36000 beat watches, it looks like Zenith’s El Primero employs conventional parallel curb pins.

In any event, I considered it discourteous to take my Jaxa tool to the case and explore further while everyone else was diverted by the canapés, so if you’ve an opinion or explanation to offer, please drop us an email.

The Workhorse

The 6R15 was displayed in a tray of diver watches. In every example, the orientation of the regulator block6 seemed very peculiar – in fact, the opposite to what I had learned of optimal setup of the Etachron system, in that it appeared the outer curb pin was closest to the stud, and the inner furthest.

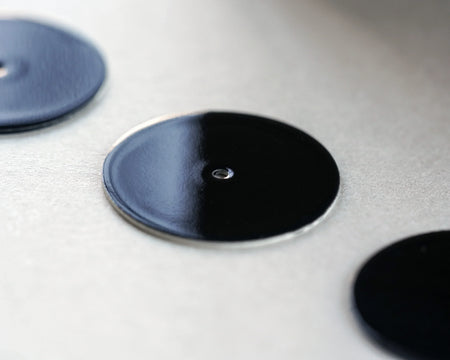

Above: Deceptive appearances! Seiko 6R15D regulator block (left) vs. Etachron regulator block (right).

Seasoned Seiko servicers may laugh at my simplicity on this one; it took a week for the penny to drop! The answer was eventually found via a copy of the technical guide for the earlier 7s26c; a large colour macro shot showing the underside of the regulator block in a helpful hairspring adjustment section at the end.

Simply put: the pins themselves are orientated in the typical arrangement, outer pin furthest from the stud, inner pin closest. It’s just that the block above them is designed to rest in the index arm with its longest side concentric with the balance staff at maximum clearance, rather than the shortest side as with the Etachron system.

Credor Fugaku

The Credor is Seiko's in house tourbillon. The tourbillon itself was on display through an open heart dial, and incredibly small. Holding this very exclusive and ostentatious timepiece in my tremulous hands - I was glad of the wire holding the loupe safely to my eye - I was surprised by how compact the whole package was, bejeweled case and all. You'd think Seiko had been making tourbillons for years!

It was wonderful to take a loupe to these watches; interesting features abounded and we left wiser for the experience! I’m not quite ready to let go of my Seiko 5 in part exchange for the Fugaku, but certainly inspired enough to hunt down another interesting fixer-upper to service.

Further reading:

Redbar Glasgow

James Porter & Son

American Watchmakers-Clockmakers Institute ‘Hairsprings’, a terrifically concise explanation of Etachron adjustment