The anOrdain A1: Decorating La Joux-Perret’s G101 Movement

May 29, 2025

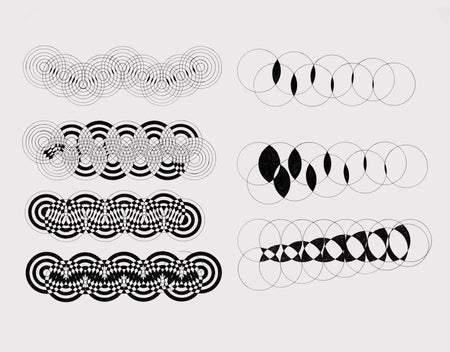

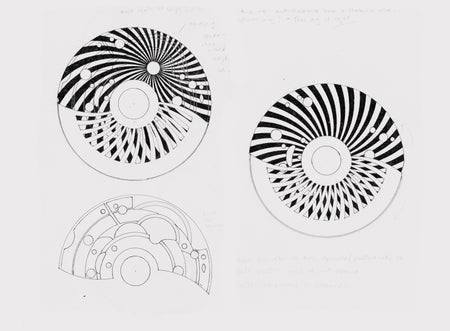

In early 2020, anOrdain approached Glasgow-based artist Rachel Duckhouse to take up a residency. The subject of movement finishing and decoration had been discussed for some time, and the prevailing view was to approach it with as few preconceived ideas as possible. The techniques in use today often rely on machinery from the 1950s, with hand-finishing filling in the rest. The team posed a question: If today’s equipment had been available then, what would the result look like? The answer combined lasers, CNC, and advanced multi-layer galvanic processes. It was Sally who suggested that Rachel’s work might be an ideal fit.

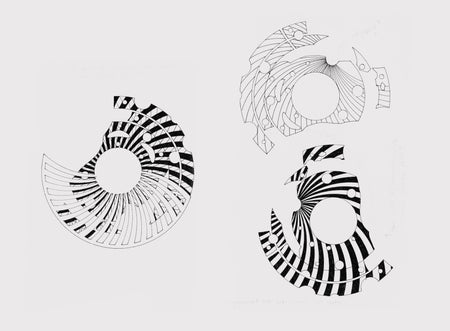

Rotor sketches

“Time has, funnily, become a big theme in my recent work. But for this, I was more wrapped up in the mechanism—the physicality of the movement.”

“Time has, funnily, become a big theme in my recent work. But for this, I was more wrapped up in the mechanism—the physicality of the movement.”

Rachel in her Glasgow studio

The Model 2 with the A1 movement

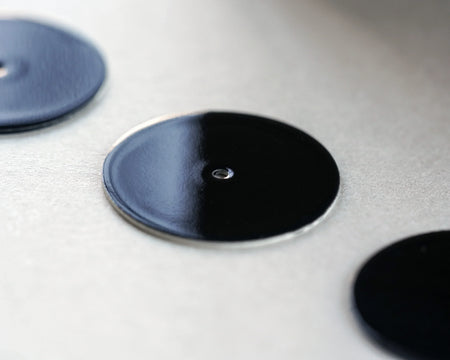

Model 1 case

Made entirely by our partners in Switzerland, the A1 is now offered as an optional movement across our Model 1 Enamel, Model 2 Enamel, and Model 2 Porcelain ranges with an exhibition caseback.