100 Years of British Military Watches - Part 2

Jan 11, 2019

Post War to Cold War

Immediately following WWII, Britain was victorious but broke. The rapid demobilisation of British forces meant that there was a lot of war surplus, and this included watches. Adverts appeared in newspapers offering surplus high-grade military watches for sale at prices that would make todays collectors weep tears of joy.

The oversupply of military watches, in relation to the reduced numbers of troops that needed them, declining military spending, and the high quality and durable nature of the watches remaining from WWII, appears to have led to something of a lull in procurement. One of the exceptions to this however are the spectacular RAF Jaeger LeCoultres, and IWC Mark 11 watches. Many watches from WWII remained in regular military use up to and beyond the 1970s.

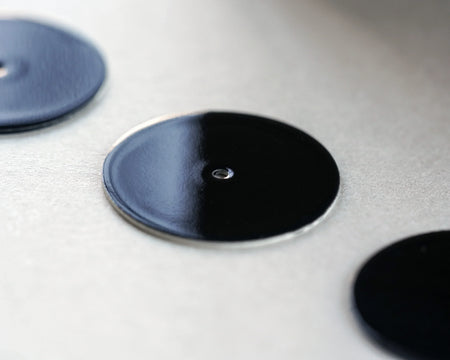

By the 1960s Britain was swinging again, and the Ministry of Defence began the procurement of the most British of military issued watches, the Smiths W10. Smiths was a British industrial conglomerate, who had produced a variety of time keeping devices for British forces in WWII, an example of which is shown below.

In 1947 they had released line of high grade, entirely British made watches, for the civilian market. The watch they produced for British military, the W10, was the only British military issued watch produced entirely in the UK, as far as I am aware.

This watch also features what is now regarded as a hallmark of mechanical military watches, the hack function. You will likely be familiar with the scene from war films of a group of soldiers about to embark on a mission, ordered by the C.O. to “synchronise watches”. The purpose of this was to have everyones’ watch running on exactly the same time, to facilitate close coordination of operations. This is what the hack function is for, to allow a watch to be set precisely and easily. Pulling out the crown leads to a small interrupter lever touching the balance wheel, allowing the seconds hand to be stopped precisely, and then restarted when the crown is pushed back in.

By the 1970s the UK military was back under some financial pressure, not least due to the ailing British economy of the day. Smiths watch production was nearing the end of its days, and a new company, Hamilton began producing the W10 that was to succeed the Smiths version, and was issued from 1973 to 1976.

This watch was manual winding with a Hamilton calibre 649 movement, which was a rebadged ETA 2750 movement, again with hack seconds, and in a suitably 1970s tonneau shaped case. The case was also of a monocoque design, which increased water resistance, and the movement could only be accessed by removing the glass.

The circled T on the dial denotes the luminous material used, which was Tritium, a mildly radioactive isotope of hydrogen with a half-life of 12 years. Although no longer glowing, this material is prone to age to a lovely creamy patina, beloved of collectors.

These watches were issued to all three services, and now is a good time to explain the various service issue codes. Firstly, and most common is the issue code number “W10” which denotes British Army issue (as seen on Smiths). Next is “0552” (as see on the above Hamilton), which is the issue code for the Royal Navy. A very small number of watches have an issue code of “0555” (see Part III, CWC section for an example) which is believed to be the issue code for the Royal Marines &/or Royal Navy. Finally, the issue code “6BB” denotes Royal Air Force issue.

By the late 1970s Hamilton itself was on the ropes due to the Quartz crisis engulfing the industry, and pulled out of the military watch supply business. However, an enterprising British employee of Hamilton, Mr Ray Mellor, their contracts director, recognised that there was still a significant demand for these watches from the Ministry of Defence. Accordingly, in the 1970s he established the Cabot Watch Company (CWC) to take over where Hamilton left off.

Using the same components and Swiss suppliers as Hamilton, CWC began supplying an essentially identical watch to the Hamilton W10, except with CWC instead of Hamilton on the dial. CWC would go on to become one the most famous later producers of British military watches, supplying everything from the ubiquitous G10, to chronographs, divers watches and even the watch issued to members of the Special Boat Service, the naval equivalent of the SAS.

In 1976 a somewhat mysterious watch was produced for the RAF. Known by collectors as the “6BB Lost Navigator” little or nothing is known about the provenance of this watch. There is no makers name, and the movement a high grade A. Schild AS 2160 17 jewel movement running at 28,800bph, with micro regulator adjuster for precision regulation. From the serial numbers, it is known that not more than 2000 of the watches were produced, and they all date from 1976. It has been suggested that the timing of the production of this watch may be significant, as it just predates the use of Quartz watches by the British military. The watch may have been turned down for wider procurement, given the end of mechanical military issued watches was fast approaching, coupled with the budgetary pressures of the time.

Given the mystery shrouding the 6BB Lost Navigator this an opportune moment to discuss another couple of “fantasy” elements of military watch collecting, that you may remember me mentioning in part one. The first of these is the so called “sterile dial”. A “sterile” dial is one which has no identifying marks on the dial. In military watch collecting lore, it is sometimes said that sterile watches are issued to special forces operating behind enemy lines. This is so that in the event of their capture, their equipment cannot be used to tie them to a particular countries armed forces, and hence the operation can be denied by the government. Whilst clearly there is evidence of such operations occurring, the numbers of individuals and hence watches involved must have been pretty small.

Another great military watch collecting myth relates to the effect of the Electro Magnetic Pulse (EMP) resulting from a thermonuclear detonation. If you are unfamiliar with EMP, this is a large burst of electromagnetic spectrum energy that radiates out from a nuclear explosion. When this hits electrical or electronic equipment, it basically fries it, making it inoperable. For this reason most military electronic equipment is specially protected against EMP.

In relation to military watches the story goes that all quartz watches within a several hundred mile radius of a nuclear bomb detonation would be destroyed by the EMP. This has led to some speculation that this was a reason why militaries continued to use mechanical as opposed to quartz watches for so long. It also led to a belief, allegedly based on an inventory list of a nuclear bunker, that many bunkers contained boxes of mechanical military watches to replace the dead quartz watches of those lucky (or unlucky) enough survive the initial nuclear blast.

Obviously, there is nothing a military watch collector would like more than to come across one of these boxes of new old stock, mint in box mechanical military watches. However, most normal people are likely to think you would have bigger things to worry than your watch breaking if nuclear bombs started going off around you.

As the end of the 1970s approached the Swiss mechanical watch industry was itself in meltdown, due to what was to be known as the “Quartz crisis”. This also meant that British military watches were on the cusp of a once in quarter of millennia change, as they too began to be powered by the revolutionary new Quartz movement. Join me in part III as we find out how the Quartz movement first appeared on the wrists of HM Armed Forces, and find out what watches British soldiers, sailor and airmen are wearing today.