Enamelling Techniques: Cloisonné

Nov 06, 2020

Enamelling has a long and illustrious history, with its first known traces dating back to Mycenaean Greece in 1500 BC. In our previous journal posts, Everything You Need to Know About Enamel Parts I & II, we delved into how enamel is used for making dials, some of the challenges faced when working with the material, as well as a brief exploration of the different types of enamel. In the next few features, we’re going to take a closer look at various enamelling methods, kicking off with cloisonné.

The term cloisonné comes from the French ‘cloison’ which translates to mean ‘partition’.

The term cloisonné comes from the French ‘cloison’ which translates to mean ‘partition’.

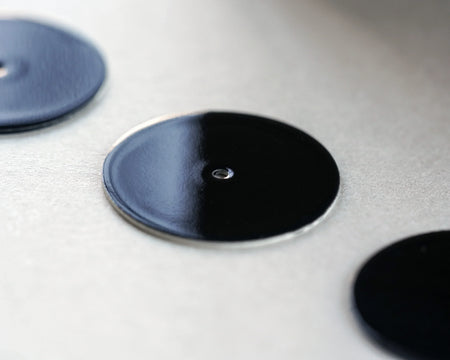

One of anOrdain's own talented enamellers, Morna Darling, applying the wettened enamel to a cloisonné base before it is sanded and fired to finish

An example of early Byzantine jewellery, 9th Century AD. The ring consists of gold, filigree and cloisonné enamel

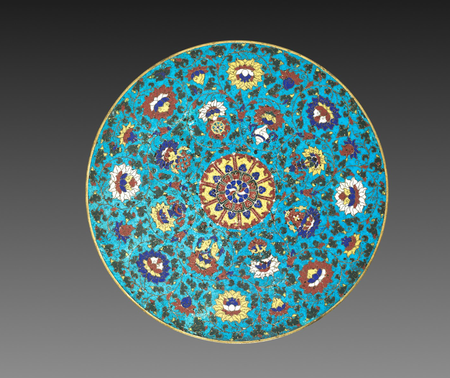

A ritual object of Tibetan Buddhism, this cloisonné disc was the base for a three-dimensional mandala. Ming Dynasty cloisonné mandala base, ca. early 15th Century AD