Enamelling Techniques: Plique-à-jour

Feb 18, 2021

In this third and final exploration of enamelling techniques, we now turn to the most technically challenging and time-consuming method – plique-à-jour.

The definition of plique-à-jour translates loosely from French to mean ‘letting in daylight’. Plique-à-jour enamelling is the application of transparent enamel to metal cells without the support of a metal backing, creating an effect reminiscent of stained glass. Often called ‘backless cloisonné’, plique-à-jour is similar to the cloisonné technique through its use of fine metal strands – usually gold or silver – to form cells that separate the different colours of enamel within the design.

Historically, plique-à-jour is believed to date back to Byzantium, to the 6th Century AD. However, due to its exceptionally fragile nature, very few examples survive from this time.

Nevertheless, the intricate enamelling method witnessed revivals throughout the centuries. One such revival occurred in the sixteenth century, as noted in renowned goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini’s The Treatises of Benvenuto Cellini on Goldsmithing and Sculpture, published in Florence in 1568. In his book, Cellini recalls an encounter with King Francis in Paris during which the king asked him to explain the enamelling method. Cellini not only provides a detailed account of the enamelling process but recalls his glee regarding his encounter with the king and court.

In her book The Art of Enamelling, Linda Darty states that Cellini explained how 'gold filigree wire was formed into designs inside an iron bowl, painted with gum tragacanth to hold them in place'. She continues, 'after inlaying the enamel [Cellini] states that "to begin with, you must only subject the enamel to a slight heat after which, when you have filled up any little openings with a second coat of enamel, you may put it in again under a rather bigger fire"'. This process is repeated until the cells are evenly full of enamel.

Historian and author Vera K. Ostoia describes the significance of Cellini's description and subsequent documentation in her essay, A Late Mediaeval Plique-à-Jour Enamel. She explains that his 'information is so much the more valuable to us since this particular technique is not discussed in earlier manuals, and since his pride in having been able to satisfy the king’s curiosity regarding it shows that it was not widely known at the time'.

Plique-à-jour fell in and out of fashion over the centuries, before becoming popular once more in the late nineteenth century, when the Russian revivalists adopted the technique for fine jewellery and tableware. Indeed, many of the masters who worked with Peter Carl Faberge also explored plique-à-jour enamelling within their own work.

During this time, plique-à-jour also became favoured in Western Europe and gaining widespread popularity within the Art Nouveau movement. Many renowned Art Nouveau artists such as René Lalique and Louis Comfort Tiffany employed plique-à-jour for various small ornaments and fine jewellery. Lalique, in particular, perfected the art of plique-à-jour, and would often pair the transparent glass with more unusual materials, such as copper, iron and aluminium, in addition to gold and silver. Bright gemstones, such as jade and amethyst, adorned many of his pieces, complimenting the transparent enamel with luxurious brilliance.

Plique-à-jour enamel was a perfect match for the sinuous lines of Art Nouveau design. Because of the delicate nature of plique-à-jour, sharp, angular shapes do not lend themselves well to the technique. Tight corners cause the metal to put pressure on the enamel and subsequently cause the glass to crack. As a result, plique-à-jour designs are often soft and curvilinear, with gentle rolling lines, much like those favoured by the Art Nouveau movement. The lightness of plique-à-jour enamel was also said to replicate the transparency found in nature - the subject of many Art Nouveau designs - and was often employed to depict flowers, leaves and insects.

Although plique-à-jour is a relatively common enamelling technique, a limited amount of information exists regarding the process and its history compared to its cloisonnéand champlevé counterparts. This scarcity of information is partly because such a small amount of plique-à-jour enamel has survived over the years and partly due to it not being so widely practised. It is a time-consuming process with a high failure rate which requires swathes of patience from those who choose to pursue the craft.

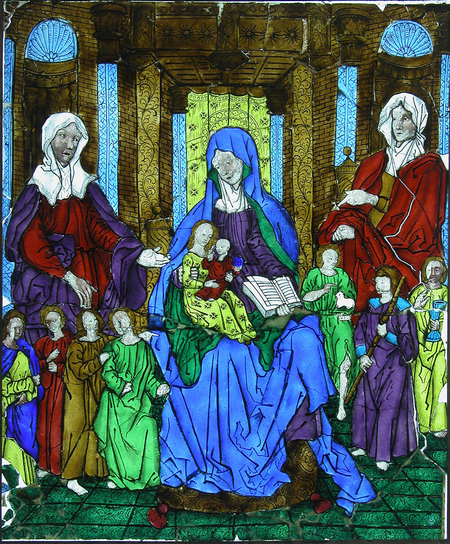

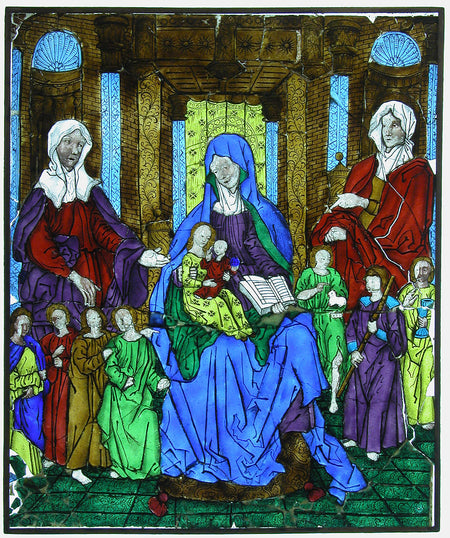

Surviving plique-à-jour plaque with the Virgin and Child, 16th C, Switzerland. The Met

Types of Plique-à-jour Enamel

There are several different approaches to choose from when practising plique-à-jour enamelling. Some plique-à-jour techniques favour a temporary backing during the initial stages of the process while others rely on surface tension to hold the enamel in place.

Pierced

Pierced plique-à-jour enamelling begins by sawing shapes from a metal sheet. A small hole is pierced through the metal to allow a jeweller's saw to cut around the desired design. When the sawing is complete, the metal drops out from the sheet, leaving an empty cavity to later fill with enamel.

Soldered Filigree

For soldered filigree plique-à-jour metal wires are constructed and soldered over a base object, such as a vase or a bowl, to form a mesh frame. Ground enamel is then applied to each cell and fired. This process is repeated until the cells are evenly full of enamel.

Methods

For both techniques, there are different ways to apply the enamel. As mentioned above, while some plique-à-jour artists choose to enamel without a temporary backing, others use various materials to support the enamel during the laying and firing, removing it from the enamelled framework once the process is complete.

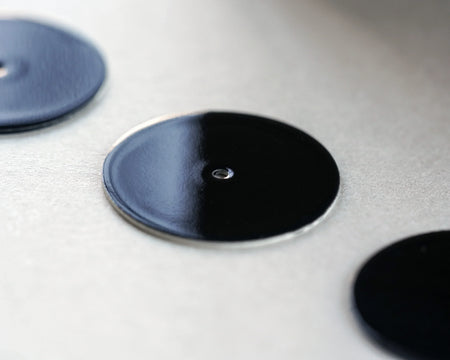

The most common of temporary backings used in plique-à-jour enamelling are mica and burnished copper foil.

Mica is a heat-resistant, relatively soft and flexible mineral material. The metal framework is placed on top of the mica to be set and inlaid with enamel. Due to the heat-resistance of mica, the framework can remain on the material during firing. Once complete, the frame is lifted from the mica, and the fired enamel is sanded down and cleaned to remove any remnants. This method suits beginners and small, flat pieces of plique-à-jour.

Another option for plique-à-jour enamelling is to use copper foil. The foil is cut and placed on the back of the framework to ensure it wraps around the base design and does not slip out of place during firing. Afterwards, once the cells are filled evenly with enamel, the copper is gently peeled away, and the enamel polished to remove any leftover fragments.

The alternative option when practising plique-à-jour enamelling is known as capillary action fill. Capillary action fill is the process of applying wet enamel to a backless metal framework, whether pierced or soldered, using a paintbrush or small spatula. It is a process which relies on surface tension between the enamel and metal to keep the enamel in place. Therefore, it is essential to create cells small enough for the enamel to sit comfortably in place, while also ensuring that the consistency of wet enamel is just right.

Plique-à-jour enamelling is an intricate, time-consuming technique that requires great patience from those who practise the craft. Although it has existed for centuries, very few early examples remain due to its fragile nature and the level of skill required to perfect the technique.

The beautiful pieces survived from the Art Nouveau movement and Russian masters of the nineteenth century demonstrate that the arduous effort involved in undertaking the craft is all worth it. As an article from 1957 titled, The History of Enamelling Technique sums up, plique-à-jour 'can fray the calmest temperament, but if you succeed in your battle, you will be rewarded with sheer beauty.'

René Lalique, ‘Dragonfly Woman’ corsage ornament, c.1897-98. Founder’s Collection, Gulbenkian