Smith's Watches

Dec 22, 2020

An introduction to British watchmaking history

Although you may have heard the saying that Great Britain is the mother of Parliaments, you might be less aware that the UK is also often seen as the mother of modern watchmaking.

From the invention of the balance spring by Robert Hook in 1664, the lever escapement devised by Thomas Mudge in 1755, to John Harwood's even-winding innovation in 1924, Britain has a legitimate claim as the home of the modern mechanical watch.

As with many things in life, throughout the years, the British horological industry has moved in a cyclical pattern. During the 17th and 18th centuries, British clock and pocket watch production and innovation dominated the global market, much like that of Switzerland and Japan today. But by the late 19th century, although Britain still produced many high-quality timekeeping instruments, the glory days were slipping into the past. A failure to adapt to modern methods of mass production saw the mastery of watch and clock-making gradually leave British shores, moving instead to Switzerland and America.

The British watch industry peaked in 1800 when it represented roughly 50% of the global market and created approximately 200,000 timepieces per year. However, by 1900, despite rapidly growing market demand, UK watch and clock production dipped, with the creation of around 100,000 pieces. Further declines were to follow into the 20th century, with only small specialist watchmakers surviving by the 1930s.

In the aftermath of WWII, however, the cycle of British watch production changed once more. The well-established British industrial conglomerate, Smiths, burst onto the booming post-war consumer market in 1947. Founded in 1851, Samuel Smith opened his first watch and clock shop in London and began a long pedigree of watchmaking. But in the aftermath of WWI, the explosion in automobile and aircraft production led Smiths to move away from horology and specialise in the production of parts for the growing British car and aviation industry.

WWII Smiths Military issued clock. Likely to have spent the war in a military or government office.

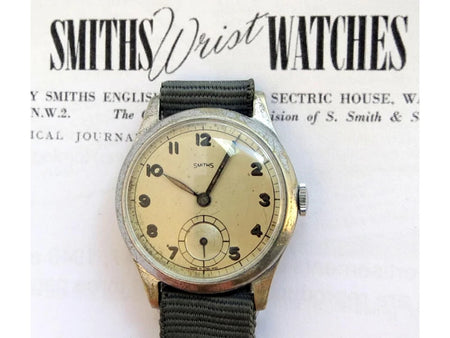

Early Smiths watch in stainless steel case. The “Made in England” on the dial indicated this was made at the Cheltenham factory, as opposed to the Welsh factory ones that read “Made in Great Britain.”

Another early Smiths watch produced in Cheltenham. Chrome-plated case showing a lot of wear, consistent with the fact that this would have been an expensive item for the average person, costing around two weeks wages at 1947 prices.

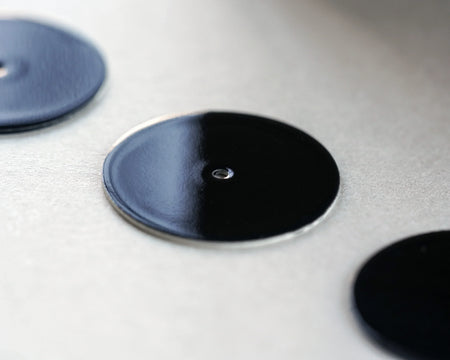

The back of an early Smith ICI silver presentation watch for long service – engraved 1945 but made in 1947.

Early gilt Smiths 12-15 movement; 12 is the ligne (size) of the movement, 15 stands for the number of jewels. Case back made by Dennison in England, with Birmingham 9ct gold 1946/47 hallmark.

Another early 9ct gold Smiths watch. Note the unusual lugs, known as Horn lugs due to their resemblance to cow horns.