History

Champlevé enamel’s history spans centuries, with the earliest known pieces dating back to 400 BCE. Celtic metalworkers of Central Europe employed the method to decorate a wide variety of objects, from jewellery and chariots to tools, weapons and harnesses. With most items from this time employing inexpensive copper as the base metal, historians believe champlevé to have gained widespread popularity as an economical alternative to cloisonné enamelling, which required ample use of expensive noble metals, such as gold and silver.

Production of champlevé enamel truly flourished in the 12th Century. Limoges, a city in south-west central France, became the epicentre of champlevé enamelling in the 1100s, with workshops set up all over the city dedicated to the craft. Limoges, known as the global capital of ‘the arts of fire’, was already a city of strong artistic heritage as a result of centuries worth of production of beautifully illustrated religious manuscripts at St. Martial’s abbey. Local artists were, therefore, already familiar with the production and use of beautiful, vibrant colours - just one of the qualities that would subsequently define Limoges champlevé enamel as some of the finest in the world.

For two centuries, enamelling workshops in Limoges thrived and the region became renowned for both the quality and quantity of its enamel production. Many of the earliest pieces depicted biblical narratives and adorned religious artefacts. Indeed, the church heavily endorsed Limoges enamelling industry.

However, it all came to an abrupt halt in 1370 with a siege on the city during the 100 Years War. Led by the Black Prince, English soldiers destroyed the last remaining enamelling workshops. Champlevé enamelling was already witnessing a decline in the region, but historians believe that the siege of 1370 dealt the industry its final blow. It would take another 100 years for the region’s traditional practice to recover.

Champlevé’s popularity, like all enamelling, has gone through peaks and troughs throughout the centuries, seeing revivals with Fabergé’s exquisite eggs and later again with the birth of Art Nouveau. Indeed, we are presently practising and experimenting with champlevé enamel here at anOrdain.

Champlevé Enamel in the 21st Century

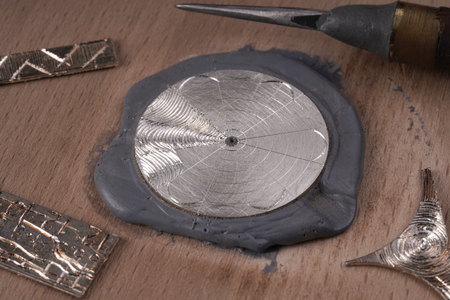

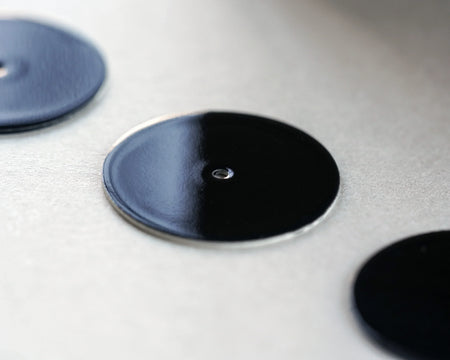

Although the practice has become increasingly sophisticated over the years with technological advancements, the method itself remains largely unchanged. The earliest champlevé enamellers, for example, would have chiselled or gouged the cells into the metal using rudimentary tools. Now, there are various techniques to choose from that offer enamellers better precision, including engraving, etching, embossing and acid bathing.

Champlevé enamelling, especially that of Limoges, is revered around the world to this day. This ancient technique has not only survived throughout the centuries but has changed little along the way and, as our enamellers continue to practise champlevé in the studio, it is the perfect embodiment of an old craft well and truly passed onto new hands.