Advantages of Thermal Bluing

“Tempering steel to blue has two practical advantages,” anOrdain watchmaker Chris Roussias explains. “Firstly, it gives the metal a good balance between hardness and strength and, secondly, the oxide layer that forms helps to protect the steel from rust.” For those reasons, he says, bluing the carbon steel of wristwatch mainsprings would have been particularly useful before modern alloys became available.

“The steel moves through a spectrum of colours as its temperature increases, ranging from a soft straw to brown, then purple, then finally blue”

The Process

The time required to complete the thermal bluing process depends on the size of the metal workpiece, and there are several ways to apply the heat. “In order of speed,” Roussias says, “the traditional alcohol lamp is the slowest, the gas torch a little faster and the electric hot plate the fastest.” For the metal to turn blue, it must reach approximately 280-300 degrees Celsius. However, as different alloys vary in the temperature at which they blue, Roussias explains that “for an aesthetic purpose such as heat-treating watch hands, it is beneficial to judge the colour by eye rather than aim for a specific temperature."

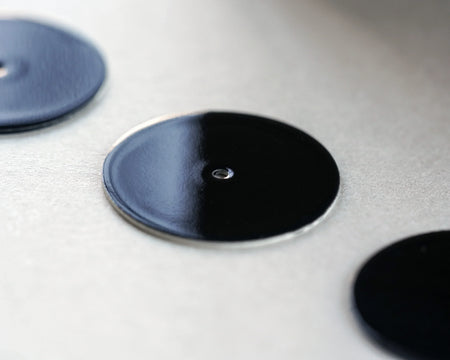

Before it reaches its final inky hue, the steel moves through a spectrum of colours as its temperature increases, ranging from a soft straw to brown, then purple, then finally blue.

Challenges

Although the process is swift once in motion, rigorous preparation is required for thermal bluing to be successful, and many factors can cause problems. “The steel needs to be in a decent state of polish and must be perfectly clean. The slightest trace of oil, dust or dirt will show up as an imperfect spot,” Roussias explains. Even once polished, it is essential to make sure the metal is clean, as alcohol stains from the cleaning process are liable to show through if not treated correctly.

Another challenge of thermally bluing steel is achieving a uniform colour, both on the individual piece and any accompanying parts, such as a set of watch hands. “Care and concentration are needed to ensure that each hour, minute and seconds hand – each a different shape and size – will actually match one another when eventually installed in the finished watch,” Roussias explains.

In order to evenly distribute the heat, the steel components are placed on a bed of brass filings. Once the hand or screw turns blue, it must be carefully checked for any imperfections. Luckily, if any flaws appear, the metal piece can be polished clean, and the process started from scratch - at no detriment to the quality of the metal.

The practice of bluing steel takes time and an exquisite eye for detail. Although the steel parts, such as anOrdain’s watch hands, are near enough miniscule, each one has undergone careful and skilled treatment, adding an extra element of care to the timepiece it adorns. And, as the anOrdain watchmakers insist of their thermally blued steel – if it can’t stand the heat, it has no place on your wrist.

This article features in Issue Two of Letters from Assynt; anOrdain’s bi-annual publication. If you enjoyed your read and would like to discover more content like this, follow the above link to sign up and receive your free copy straight to your door or inbox.